The first lyric in the Bowie Blackstar song is "in the villa of Ormen”following the line “stands a solitary candle". Ormen is the name of a village in Norway. "Ormen" actually means "Serpent" in Norwegian. The most famous example of this name's use in history is the "Ormen Lange" which means the "Long Serpent" and was the name of a viking ship. This is a reference that corrolates with Christianity since the story of a king that violently rejected Christ during a crusade in 8th century AD. The lyric can be recognized as Bowie telling you to come to the town of the serpent. Not only is it a possiblity of this bit being referencing the Norwegian story but also something about the Villa of Ormen being the town or village of the Serpent evokes an image of the Hopi pueblos and their Snake Dance ceremony ceremony. The rustic wooden huts that are shown in the video seem like a kiva too, since the sunlight is shining as if they're underground. Even though kivas are generally for men and underground, with earthen walls and wooden roof and a ladder to go down, the last ritual with the women shows a dark, circular underground chamber that resembles one. The line "villa of Ormen" means house of Serpent(s), and the Egyptian deity Apep is depicted as a giant serpent and represents darkness and chaos. Basically Apep is evil. Could Bowie be saying that there is a "solitary candle" or fire igniting in the "house of serpent" or darkess/chaos? The world does seem to be getting increasingly dark and chaotic... Then he says "in the center of it all...your eyes" as if we are the ones witnessing/taking part in it all.

Ormr inn Langi in Old Norse (The Long Serpent) Ormen Lange in Norwegian, Ormurin Langi in Faroese was one of the most famous of the Viking longships. It was built for the Norwegian King Olav Tryggvason, and was the largest and most powerful longship of its day. In the late 990s King Olav was on a "Crusade" around the country to bring Christianity to Norway. When he was traveling north to Hålogaland he came to a petty kingdom in today's Skjerstad, where the king named Raud the Strong refused to convert to Christianity. A battle ensued, during which Saltstraum, a maelstrom that prevented reinforcements to the king's men, forced King Olav to flee. He continued up north but returned some weeks later when the maelstrom had subsided. Olav won the battle, captured Raud, and gave him two choices: die or convert. The Sagas say that Olav tried to convert him but Raud cursed the name of Jesus, and the King became so enraged that he stuck a kvanstilk (a pipe) down his throat and shoved a snake into it, then a burning iron to force the snake down his throat. The snake ate its way out of the side of the torso of Raud and killed him. After the victory Olav confiscated Raud's riches, not least of which was Raud's ship, which he rechristened Ormen (The Serpent). He took it to Trondheim and used it as a design for his own new ship, which he made a couple of "rooms" longer than Ormen and named Ormen Lange. The ship reportedly had 34 rooms, i.e., was built with 34 pairs of oars, for a crew of 68 rowers (and additional crew members). Extrapolating from archeological evidence (e.g., the Gokstad ship), this would make Ormen Lange nearly 45 metres (148 ft) long. The ship’s sides were unusually high, "as high as that of a Knarr". Ormen Lange was the last ship to be taken in the Battle of Svolder, where Olav was killed (although his body was never found—some stories tell of the king jumping into the water either sinking due to the weight of his armour or escaping in the confusion) by a coalition of his enemies in the year 1000. Its story is told in a traditional Faroese ballad, or Kvæði, called "Ormurin Langi".

The most widely publicized of Hopi rituals was the Snake Dance ceremony, held annually in late August, during which the performers dance with live snakes in their mouths. The dance is thought to have originated as a water ceremony because snakes were the traditional guardians of springs. Today, it is primarily a rain ceremony and to honor Hopi ancestors. The tribe regards snakes as their "brothers" and rely on them to carry their prayers for rain to the gods and spirits of their ancestors. The Snake Dance ceremony requires two weeks of ritual preparation, during which time the snakes are gathered and watched over by children until time for the dance. On the last day of the 16-day celebration, the dance is performed. By percentage of the local snake population most are rattlesnakes, but all are handled freely. Before the dance begins the participants take an emetic (probably a sedative herb) which is not an anti-venom and then dance with the snakes in their mouths. There is usually an Antelope Priest in attendance who helps with the dance, sometimes stroking the snakes with a feather or supporting their weight. The dance includes swaying, rattles, a guttural chant and circling of the plaza with snakes. After the dance the snakes are released in the four directions to carry the prayers of the dancers. Although part of the Snake Dance ceremony is performed for the tribe, this is only a portion of a lengthy ceremony, most of which is conducted privately in kivas. The Hopi women make up extra supplies of baskets and pottery to offer for sale at the time of the Snake Dance ceremony because they know many tourists are coming to buy them, otherwise they get no revenue from the occasion. No admission is charged, and the snake priests themselves seriously object to having Hopi citizens charge anything for the use of improvised seats of boxes, etc., on the near-by house tops. The writer has seen tourists so crowd the roofs of the Hopi homes surrounding the dance plaza that she feared the roofs would give way, and has also observed that the resident family was sometimes crowded out of all "ring-side" seats. No wonder the small brown man of the house has in some cases charged for the seats. What white man would not? Yet the practice is considered unethical by the Hopi themselves and is being discontinued. We know that this weird, the pagan Snake Dance ceremony was performed with deadly earnestness when white men first penetrated the forbidding wastelands that surround the Hopi. And we have every reason to believe that it has gone on for centuries, always as a prayer to the gods of the underworld and of nature for rain and the germination of their crops. The writer has observed these ceremonies in the various Hopi villages for the past twenty years, some with hundreds of spectators from all over the world, others in more remote villages, with but a mere handful of outsiders present. She is personally convinced that the Snake Dance ceremony is no show for tourists but a deeply significant religious ceremony performed definitely for the faithful fulfillment of traditional magic rites that have, all down the centuries, been depended upon to bring these desert-dwellers the life-saving rain and insure their crops. They have long put their trust in it, and they still do so. Are there any unbelievers? Yes, to be sure; but not so many as you might think. There are unbelievers in the best, of families, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Hopi, but the surprising thing is that there are so many believers, at least among the Hopi. But there are still some out there. The Snake Dance ceremony, so-called, is the culmination of an eight-days' ceremonial, an elaborate prayer for rain and for crops. Possibly something of the significance of parts of its complicated ritual may have been forgotten, for some of our thirst for knowledge on these points goes unquenched, in spite of the courteous explanations the Hopi give when our queries are sufficiently courteous and respectful to deserve answers. And possibly some of the things we ask about are "not for the public" and may refer to the secret rituals that take place in the kivas, as in connection with many of their major ceremonials. We do know that the dramatization of their Snake Myth constitutes part of the program. This myth has many variations. The writer, personally, treasures the long story told her by Dr. Fewkes, years ago, and published in the Journal of American Ethnology and Archaeology, Vol. IV., 1894, pages 106-110. But here shall be given the much shorter and very adequate account of Dr. Colton, abbreviated from that of A.M. Stephen: "To-ko-na-bi was a place of little rain, and the corn was weak. Tiyo, a youth of inquiring mind, set out to find where the rain water went to. This search led him into the Grand Canyon. Constructing a box out of a hollow cottonwood log, he gave himself to the waters of the Great Colorado. After a voyage of some days, the box stopped on the muddy shore of a great sea. Here he found the friendly Spider Woman who, perched behind his ear, directed him on his search. After a series of adventures, among which he joined the sun in his course across the sky, he was introduced into the kiva of the Snake people, men dressed in the skins of snakes. The Snake Chief said to Tiyo, 'Here we have an abundance of rain and corn; in your land there is but little; fasten these prayers in your breast; and these are the songs that you will sing and these are the prayer-sticks that you will make; and when you display the white and black on your body the rain will come.' He gave Tiyo part of everything in the kiva as well as two maidens clothed in fleecy clouds, one for his wife, and one as a wife for his brother. With this paraphernalia and the maidens, Tiyo ascended from the kiva. Parting from the Spider Woman, he gained the heights of To-ko-na-bi. He now instructed his people in the details of the Snake ceremony so that henceforth his people would be blessed with rain. The Snake Maidens, however, gave birth to Snakes which bit the children of To-ko-na-bi, who swelled up and died. Because of this, Tiyo and his family were forced to emigrate and on their travels taught the Snake rites to other clans." Most of the accounts tell us that later only human children were born to the pair, and these became the ancestors of the Snake Clan who, in their migrations, finally reached Walpi, where we now find them, the most spectacular rain-makers in the world. Another fragment of the full Snake legend must be given here to account for what Dr. Fewkes considers the most fearless episode of the Snake Ceremonial—the snake washing: "On the fifth evening of the ceremony and for three succeeding evenings low clouds trailed over To-ko-na-bi, and Snake people from the underworld came from them and went into the kivas and ate corn pollen for food, and on leaving were not seen again. Each of four evenings brought a new group of Snake people, and on the following morning they were found in the valleys metamorphosed into reptiles of all kinds. On the ninth morning the Snake Maidens said: 'We understand this. Let the Younger Brothers (The Snake Society) go out and bring them all in and wash their heads, and let them dance with you.'" Thus we see in the ceremony an acknowledgment of the kinship of the snakes with the Hopi, both having descended from a common ancestress. And since the snakes are to take part in a religious ceremony, of course they must have their heads washed or baptized in preparation, exactly as must every Hopi who takes part in any ceremony. The meal sprinkled on the snakes during the dance and at its close is symbolic of the Hopi’s prayers to the underworld spirits of seed germination; and thus the Elder Brothers bear away the prayers of the people and become their messengers to the gods, to whom the Elder Brothers are naturally closer, being in the ground, than are the Younger Brothers, who live above ground. Rather a delicately right idea, isn't it, this inviting of the Elder Brothers, however lowly, to this great religious ceremonial which commemorates the gift of rain-making, as bestowed by their common ancestress, and perpetuates the old ritual so long ago taught by the Snake Chief of the underworld to Tiyo, the Hopi youth who bravely set out to see where all the blessed rain water went, and came back with the still more blessed secrets of whence and how to make it come. Nine days before the public Snake Ceremony, the priests of the Antelope and Snake fraternities enter their respective kivas and hang over their hatchways the Natsi, a bunch of feathers, which, on the fifth day is replaced by a bow decorated with eagle feathers. This first day is occupied with the making of prayer-sticks and in the preparation of ceremonial paraphernalia. On the next four days, ceremonial snake hunts are conducted by the Snake men. Each day in a different quarter of the world, first north, next day west, then south, then east. It is an impressive sight, this line of Snake priests, bodies painted, pouches, snake whips, and digging sticks in hand, marching single file from their kiva, through the village and down the steep trail that leads from the mesa to the lowlands. When a snake is found under a bush or in his hole, the digging stick soon brings him within reach of the fearless hand; then sprinkling a pinch of corn meal on his snakeship and uttering a charm and prayer, the priest siezes the snake easily a few inches back of the head and deposits him in the pouch. Should the snake coil to strike, the snake whip (two eagle feathers secured to a short stick) is gently used to induce him to straighten out. At sunset they return in the same grim formation, bearing the snake pouches to the kiva, where four jars (not at all different from their water jars) stand ready to receive the snakes and hold them till the final or ninth day of the ceremony. On the next three mornings, just before dawn, in the Antelope Kiva, is held the symbolic marriage of Tiyo and the Snake Maiden, followed by the singing of sixteen traditional songs. Just before sunset of the eighth day, the Antelope and Snake priests give a public pageant in the plaza, known as the Antelope or Corn Dance. It is a replica of the Snake Dance ceremony, but shorter and simpler, and here corn is carried instead of snakes. On the morning of the ninth and last day occurs the Sunrise Corn Race, when the young men of the village race from a distant spring to the mesa top. The whole village turns out to watch from the rim of the mesa, and great merriment attends the arrival of the racers, the winner receiving some ceremonial object, which, placed in his corn field, should work as a charm and insure a bumper crop. In 1912, Dr. Byron Cummings witnessed a more interesting sunrise race than the writer has ever seen or heard described by any other observer. An aged priest stood on the edge of the mesa, before the assembled crowd of natives and visitors, and gave a long reverberating call, apparently the signal for which the racers were waiting, for away across the plain below and to the right was heard an answering call, and from the left and far away, another answer. Eagerly the large crowd watched to catch the first glimpse of the approaching racers, for there was no one in sight for some time, from the same direction of either of the exotic answering calls. Finally mere specks in the distance to the right resolved themselves into a line of six men running toward the mesa. As they came within hailing distance they were greeted by the acclamations of the watchers. These runners were Snake priests, all elderly men, and as each in turn reached the position of the aged priest at the mesa edge, he received from that dignitary a sprinkling of sacred meal and a formal benediction, then passed on to the Snake Kiva. Before the last of these had appeared, began the arrival of the young athletes from across the plain to the left. Swiftly them came, and gracefully, their lithe brown bodies glistening in the early sunlight, across the level lowland, then up the steep trail, to be met at the mesa edge by a picturesque individual carrying a cow bell and wearing a beautiful garland of fresh yellow squash blossoms over his smooth flowing, black hair, and a girdle of the same lovely flowers round his waist, with a perfect blossom over each ear completing his unique decoration. As the athletes, one at a time, joined him they fell into a procession and, led by the flower bedecked individual, they moved gracefully in a circle to the rhythmic time of a festive chant and the accompaniment of the cow bell. When the last racer had arrived, they were led in a sort of serpentine parade toward the plaza. But before they reached that point they encountered a waiting group of laughing women and girls in bright-colored shawls, whose rollicking role seemed to be that of snatching away from the young men the stalks of green corn, squash, and gourds they had brought up from the fields below. The scene ended in a merry skirmish as the crowd dispersed. Later, Dr. Cummings unobtrusively followed the tracks of the priests back along their sunrise trail and out across the desert for more than two miles, to find there a simple altar and nine fresh prayer-sticks. About noon occurs the snake washing in the kiva. This is not for the public gaze. If one knows no better than to try to pry into kiva ceremonies, he is courteously but firmly told to move along.

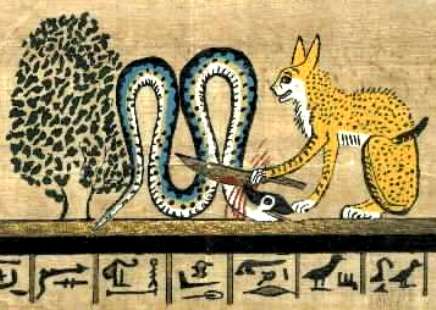

A few white men have been permitted to see this ceremony, among them, Dr. Fewkes; an extract from his description of a snake washing at Walpi follows: "The Snake priests, who stood by the snake jars which were in the east corner of the room, began to take out the reptiles and stood holding several of them in their hands behind Supela (the Snake Priest), so that my attention was distracted by them. Supela then prayed, and after a short interval, two rattlesnakes were handed him, after which venomous snakes were passed to the others, and each of the six priests who sat around the bowl held two rattlesnakes by the necks with their heads elevated above the bowl. A low noise from the rattles of the priests, which shortly after was accompanied by a melodious hum by all present, then began. The priests who held the snakes beat time up and down above the liquid with the reptiles, which, although not vicious, wound their bodies around the arms of the holders. "The song went on and frequently changed, growing louder, and wilder, until it burst forth into a fierce, blood-curdling yell, or war cry. At this moment the heads of the snakes were thrust several times into the liquid, so that even parts of their bodies were submerged, and were then drawn out, not having left the hands of the priests, and forcibly thrown across the room upon the sand mosaic, knocking down the crooks and other objects placed about it. As they fell on the sand picture, three Snake priests stood in readiness, and while the reptiles squirmed about or coiled for defense, these men with their snake whips brushed them back and forth in the sand of the altar. The excitement which accompanied this ceremony cannot be adequately described. The low song, breaking into piercing shrieks, the red-stained singers, the snakes thrown by the chiefs and the fierce attitudes of the reptiles as they lashed on, the sand mosaic, made it next to impossible to sit calmly down and quietly note the events which followed one another in quick succession. The sight haunted me for weeks afterward, and I can never forget this wildest of all the aboriginal rites of this strange people, which showed no element of our present civilization. It was a performance which might have been expected in the heart of Africa rather than in the American Union, and certainly one could not realize that he was in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century. The low, weird song continued while other rattlesnakes were taken in the hands of the priests, and as the song rose again to the wild war cry, these snakes were also plunged into the liquid and thrown upon the writhing mass which now occupied the place of the altar. Again and again this was repeated until all the snakes had been treated in the same way, and reptiles, fetishes, crooks, and sand were mixed together in one confused mass. As the excitement subsided and the snakes crawled to the corners of the kiva, seeking vainly for protection, they were pushed back in the mass, and brushed together in the sand in order that their bodies might be thoroughly dried. Every snake in the collection was thus washed, the harmless varieties being bathed after the venomous. In the destruction of the altar by the reptiles, the snake ti-po-ni (insignia) stood upright until all had been washed, and then one of the priests turned it on its side, as a sign that the observance had ended. The low, weird song of the snake men continued, and gradually died away until there was no sound but the warning rattle of the snakes, mingled with that of the rattles in the hands of the chiefs, and finally the motion of the snake whips ceased, and all was silent.” Several hours later these snakes are used in the public Snake Dance ceremony ceremonies, and until that time they are herded on the floor of the kiva by a delegated pair of snake priests assisted by several boys of the Snake Clan, novices, whose fearless handling of the snakes is remarkable. Already (on the eighth day) in the plaza has been erected the Kisa, a tall conical tepee arrangement of green cottonwood boughs, just large enough to conceal the man who during the dance will hand out the snakes to the dancers. Close in front of the Kisa is a small hole made in the ground, covered by a board. This hole symbolizes the sipapu or entrance to the underworld. At last comes the event for which the thronged village has been waiting for hours, and for which some of the white visitors have crossed the continent. Just before sundown the Antelope priests file out of their kiva in ceremonial array—colorfully embroidered white kilts and sashes, bodies painted a bluish color with white markings in zigzag lines suggestive of both snakes and lightning, chins painted black with white lines through the mouth from ear to ear, white breath feathers tied in the top of their hair, and arm and ankle ornaments of beads, shells, silver, and turquoise. Led by their chief, bearing the insignia of the Antelope fraternity and the whizzer, followed by the asperger, with his medicine bowl and aspergill and wearing a chaplet of green cottonwood leaves on his long, glossy, black hair, they circle the plaza four times, each time stamping heavily on the sipapu board with the right foot, as a signal to the spirits of the underworld that they are about to begin the ceremony. Now they line up in front of the Kisa, their backs toward it, and await the coming of the Snake priests, for these Antelope priests, with song and rattle, are to furnish the music for the Snake Dance ceremony ceremony. There is an expectant hush and then come the Snake priests, up from their kiva in grim procession, marching rapidly and with warlike determination. You would know them to be the Snake priests rather than the Antelope fraternity by the vibration of their mighty tread alone, even if you did not see them. Their bodies are fully painted, a reddish brown decorated with zigzag lightning symbols and other markings in white. The short kilt is the same red-brown color, as are their mocassins, the former strikingly designed with the snake zigzag and bordered above and below this with conventionalized rainbow bands. Soft breath feathers, stained red, are worn in a tuft on the top of the head, and handsome tail feathers of the hawk or eagle extend down and back over the flowing hair. A beautiful fox skin hangs from the waist in the back. Their faces are painted black across the whole mid section and the chins are covered with white kaolin—a really startling effect. Necks, arms, and ankles are loaded with native jewelry and charms, sometimes including strings of animal teeth, claws, hoofs, and even small turtle shells for leg ornaments, from all of which comes a great rattling as the priests enter the plaza with their energetic strides. Always a hushed gasp of admiration greets their entrance,—an admiration mixed with a shudder of awe. Again the standard bearer, with his whizzer or thunder-maker, leads, followed by the asperger, and we hear the sound of thunder, as the whizzer (sometimes called the bull-roarer) is whirled rapidly over the priest’s head. The chapleted asperger sprinkles his charm liquid in the four directions, first north, then west, south, and east. They circle the plaza four times, each stamping mightily upon the cover of the sipapu as they pass the Kisa. Surely, the spirits of the underworld are thus made aware of the presence of the Snake Brotherhood engaged in the traditional ritual. Incidentally, this Snake Dance ceremony is carried on in the underworld on a known date in December, and at that time the Hopi Snake men set up their altar and let the spirits know that they are aware of their ceremony and in sympathy with them. Now the procession lines up facing the Antelope priests in front of the Kisa, and the rattles of both lines of priests begin a low whirr not unlike the rattle of snakes. All is perfectly rhythmic and the Snake priests, with locked fingers, sway back and forth to the music, bodies as well as feet keeping time, while the Antelopes mark time with a rhythmic shuffle. At last they break into a low chant, which increases in volume, and rising and falling goes on interminably. At last there is a pause and the Snake priests form into groups of three, a carrier, an attendant, and a gatherer. Each group waits its turn before the Kisa. The carrier kneels and receives a snake from the passer, who (with the snake bag) sits concealed within the Kisa. As he rises, the carrier places his snake between his lips or teeth, usually holding it well toward the neck, but often enough near the middle, so that its head may sometimes move across the man’s face or eyes and hair, a really harrowing sight. The attendant, sometimes called the hugger, places his left arm across the shoulder of the first dancer and walks beside and a step behind him, using his “feather wand” or “snake whip” to distract the attention of the snake. Just behind this pair walks their gatherer, who is alertly ready to pick up the dropped snake, when it has been carried four times around the dance circle; on occassion it is dropped even sooner. The dance step of this first pair is a rhythmic energetic movement, almost a stamping, with the carrier dancing with closed eyes. The gatherer merely walks behind, and is an alertly busy man. The writer has seen as many as five snakes on the ground at once, some of them coiling and rattling, others darting into the surrounding crowd with lightning rapidity, but never has she seen one escape the gatherer, and just once has she seen a snake come near to making its escape. This was during the ceremony at Hotavilla last summer (1932); the spectators had crowded rather close to the circle, and several front rows sat on the ground, in order that the dozens of rows back of them might see over their heads. As for the writer, she sat on a neighboring housetop, well out of the way of rattlers, red racers, rabbit snakes, and even the harmless but fearsome-looking bull snake from 3 to 5 feet long. Often the snake starts swiftly for the side lines, but always without seeming haste the gatherer gets it just as the startled spectators begin a hasty retreat. If the snakes coils, meal is sprinkled on it and the feather wand induces it to straighten, when it is picked up. But this time the big snake really got into the crowd, second or third row, through space hurriedly opened for him by the frightened and more or less squealing white visitors. He was depicted as a huge serpent often with tightly compressed coils to emphasis his huge size. In funerary texts he is usually shown in the process of being dismembered in various ways. In a detailed depiction in the tomb of Ramesses VI twelve heads are painted above the head of the snake representing the souls he has swallowed who are briefly freed when his is destroyed, only to be imprisoned again the following night. In an alternative depiction inscribed in a number of tombs of private individuals Hathor or Ra is transformed into a cat who slices the huge serpent with a knife. The serpent was also represented by a circular ball, the “evil eye” of Apep, in numerous temple scenes. Apep was known by many epithets, such as “the evil lizard”, “the encircler of the world”, “the enemy” and “the serpent of rebirth”. He was not worshipped, he was feared, but was possibly the only god (other than The Aten during the Amarna period) who was considered to be all powerful. He did not require any nourishment and could never be completely destroyed, only temporarily defeated. Apep led an army of demons that preyed on the living and the dead. To defeat this malevolent force a ritual known as “Banishing Apep” was conducted annually by the priests of Ra. An effigy of Apep was taken into the temple and imbued with all of the evil of the land. The effigy was then beaten, crushed smeared with mud and burned. Other rituals involved the creation of a wax model of the serpent which was ritually dismembered and the burning of a papyrus bearing an image of the snake. The “Book of Apophis” is a collection of magical spells from the New Kingdom which were supposed to repel or contain the evil of the serpent.

(Aapep, Apepi or Apophis) was the ancient Egyptian spirit of evil, darkness and destruction who threatened to destroy the sun god Ra as he travelled though the underworld (or sky) during the night.Ironically, it turns out that originally Set and Mehen (the serpent headed man) were given the job of defending Ra and his solar barge. They would cut a hole in the belly of the snake to allow Ra to escape his clutches. If they then failed, the world would be plunged into darkness. However, in later periods Apep was sometimes discovered to be and who was after all a god of chaos. In this case a variety of major and minor gods and goddesses (including Isis, Neith, Serqet (Selket), Geb, Aker and the followers of Horus) protected Ra from this all consuming evil. The dead themselves (in the form of the god Shu) could also fight Apep to help maintain Ma´at (order). Like Set, Apep was also associated with various frightening natural events such as unexplained darkness such as solar eclipse, storms and earthquakes. They were both linked to the northern sky (a place that the Egyptians considered to be cold, dark and dangerous) and they were both at times associated with Taweret, the demon-goddess. However, unlike Set he was always a force for evil and could not be reasoned with. Apep is not mentioned by name until the Middle Kingdom, but depictions of large serpents on Predynastic pottery may relate to him or to any of the variety of serpent gods or demons who appear in early texts (such as the Pyramid Texts) as representatives of evil or chaos. However, the mythology surrounding him largely developed during the New Kingdom in funerary texts such as the Duat (or Amduat). Apep is known as the “eater of souls.” Discover the legends and myths and religious beliefs surrounding immortal Apep, the Egyptian serpent god of evil, chaos and destruction who dwelled in eternal darkness. Apep was a god who appeared in the form of a serpent. The monstrous Apep, also called Apothis, was described occasionally as a huge crocodile but usually as a highly dangerous, gigantic snake who swam in the dark waters of the Underworld. Apep constantly threatened divine order and was the mortal enemy of Ra, the Sun God. The god Ra was believed to traverse the sky each day in a sun boat and pass through the realms of the underworld each night on another solar barge and during his nightly travels in the terrifying Underworld Ra was attacked by the serpent god Apep. Apep represented a demonic obstacle to the daily resurrection of the sun. Occasionally he would be victorious in his battles with Ra the solar god and his entourage of gods, and the world would be plunged into darkness. The ancient Egyptians believed that these victories allowed storms, darkness, rain and the terrifying eclipse of the sun to occur. They believed that prayers, incantations and magic spell would help Ra and the gods in their endless nightly fight on their Sun Boat against Apep. Apep the evil destroyer was never worshipped, quite the reverse. Most temple rituals of ancient Egypt were aimed correcting chaos and restoring order to the world. Because Apep was immortal he was able to emerge unscathed from any defeats by the gods. It was therefore important to the Egyptians to offer prayers and spells to help the gods overcome Apep the evil serpent. The “Book of the Overthrowing of Apep” provided temple visitors with a spell for repelling negativity, which was symbolized by the solar god Ra defeating Apep. These rituals and incantations were enacted nightly by the priests and Egyptians and were thought to help ensure the victory of Ra in his life-and-death struggle with darkness. Each year, a dangerous ritual called the “Banishing of Apep” would be held by the priests of the sun god Ra. It involved a lot of interesting rituals that would degrade the god. The “Books of Overthrowing Apep” provided the priests with details about the proper destruction of Apep and instructions were provided for: Spitting Upon Apep Defiling Apep with the Left Foot Taking a Lance to Smite Apep Fettering the God Taking a Knife to Smite Apep Putting Fire Upon Apep The priests first created an effigy of the god of evil, chaos and destruction. The effigy was taken to the center of the sun temple and the priests would pray that all the evil and wickedness in Egypt would go into the effigy. The effigy of Apep would then be attacked and defiled. The priests spat on the effigy, beat it with sticks, hacked at it with weapons and eventually burned and destroyed it. The acts of dishonoring, dismembering and disposing of the effigy were seen as important and dangerous duty of the ancient Egyptian priests and increased their power in Egypt. In ancient Egyptian mythology there are legends concerning the defeat of Apep by a great cat. The cat goddess Bastet represented both the home and the domestic cat but was also represented in the war-like aspect of a lioness, lynx or cheetah. Cat Goddesses were revered for both their powers of protection and their skills as fierce combatants. Mau and Bastet, who are both cat goddesses, were credited for killing the powerful and the evil snake god Apep. The terrible serpent god was also seen as a potential barrier to the souls of the dead succeeding in their journey through the Underworld to the Afterlife. The priests therefore created various spells as well as rituals for the ceremonies. These rituals involved blood and violence to cast away the evil God named Apep. He was a destroyer and they wanted to destroy him. We can all understand that David Bowie’s last album is constantly referencing life and death. Actually, some elements might be referring to his time in Germany, when he was heavily influenced by the classical art scene (first thing you learn in art history is about the symbolism of candles in oil paintings in relation to time and the role of the skull). An artist would use items like a skull, timepiece, snuffed out candle to represent the passage of time. The candle, it’s a big one and has lots of meanings. It can indicate the passing of time, faith in God (when its burning). When extinguished, it means death, or the loss of virginity, and the corruption of matter. It can symbolize light in the darkness of a lonely individual, or the light of Christ, purification or cleansing. The video literally shows a solitary candle it’s not even certain that light symbolizes good.